Sometime around the middle of 2005, I noticed my voice was getting weaker. Nothing dramatic occurred (that is why I cannot remember a specific date). Since I had done public speaking throughout my life, any change in voice was readily noticeable to me. In fact, I became aware of my “voice problem” long before my wife noticed it.

Again, it was nothing dramatic that immediately demanded that I change occupation. Many years previously I had learned the importance of things like timing, vocal emphasis, inflections, and pauses. Those things were practiced so frequently that they became second nature to me. I did not have to think to do them; I just did them. I did not have to plan and prepare to do such things as I made preparation. As I spoke, it was obvious what I should do and when I should do it. I could tell by the audience’s facial reactions what things were effective in communicating my thoughts. Though (as with all who deliver public speeches) I had some weaknesses that I could not ignore, I had no major problems. My voice was adequate for most situations, and it served me well.

I never had a strong voice that easily carried in every circumstance. Though I had to be conscious of over-using my voice, public speaking was never a problem for me. However, when I noticed the speaking problem, it soon became apparent that I could not assume I would use the verbal skills that were natural to me. As I would discover, no amount of personal effort could or would prevent my speaking problems.

It began as a personal frustration. In time (a matter of weeks) my personal frustration became a noticeable problem. With the passing of more time, the noticeable problem became a handicap. Eventually, my projection for public speaking became impossible. The inevitable had to be accepted!

Frustration became weariness.

Weariness became a noticeable problem.

Finally, the noticeable problem ended public speaking.

Why? At first I began to lose skills like inflection.

Then I began dropping syllables and slurring words.

The progression led to (“on my feet”) deciding an alternate way to say

something because I knew I could not pronounce a word.

Finally, trying to project and express my thoughts required more energy

than I had. Though I wanted to try,

I simply could not easily and understandably project.

On

In conjunction with projecting/speaking problems in 2005, I began to fall. Never once in my mind did I associate my voice limitations and my falling. In fact, the voice limitations were only a frustration when the falling began. I associated my falling with returning clumsiness (I was clumsy as a child).

However, the falls began to be more serious. In March of 2005, I fell in a large dark room. I had been in that room without lights many times. When I fell, I thought I was about to bump into an unknown object. My instincts instantly reacted, suddenly I lost my balance, and quickly I was on the floor.

This fall was shocking and confusing. Nothing was there! There was no reason to dodge! The result: a severely bruised right thigh. As I lay dazed on the floor, I asked myself, “How did that happen?” The resulting bruise was so large and deep that it was painfully difficult to walk.

Later there was the fall that resulted in cuts and bleeding. Still later came the fall that dislocated my left shoulder.

Understanding the

Problem

Before the age of 65, I had been many places and done a number

of things. What I now share is not

shared to brag (I have nothing to

brag about), but this is stated as an example of how much immediate transition

Joyce and I faced. I was born in

We enjoyed those experiences so much that a prominent

retirement option we seriously considered was to be a “relief couple.”

Had that retirement option developed,

we would have temporarily replaced American families in other countries who came

back to the

Our considerations and options would change quickly.

My primary care doctor, Dr. Michael Cole (who is my friend and encourager as well as my doctor), suggested we explore my balance problems. This search was to be a part of my annual medical checkup. Neither he nor I expected to find anything significant. The plan: locate the cause of my balance problems by a process of elimination, and address the problem.

On

On July 1 he called me.

A sobered, regretful voice told me the

During this period the speech problem and the balance problems

grew worse. Likely, at this time,

my problems were not noticeable to others.

Dr. Cole scheduled the first available appointment with Dr. Tremwel.

The first thing Dr. Tremwel did was observe me walk. The “walk” was less than ten steps! She told me that if I did not address some walking problems, I would be in a wheelchair in a year.

Then she scheduled a series of tests to determine the precise

problem. I gave so much blood to be

tested that I thought I needed a transfusion!

The electric stimulus test was loads of fun because I am so sensitive to

electricity!

The first results were inconclusive. Fortunately, enough blood remained to be retested. Dr. Tremwel requested that they look for specific things that might reveal the problem.

Finally, the results permitted her to make a diagnosis (spinal

cerebellum atrophy # 8). It was the

typical “good news and bad news” report.

The good news: the problem would not kill me quickly—in fact,

I could live a normal life span!

Of all the identified types of this problem, I had the least destructive

kind.

The bad news: the problem is genetic, and there is no treatment for the cause. Only the symptoms can be treated as they occur. This rare condition exists in so few people that little research is done on the problem.

The objective: slow the problem down through physical therapy.

Personally slow down (I did not consider myself unduly fast).

My past practices (exercise routines, watching my weight, etc.) were a

definite plus.

My first major transition involved the unthinkable: do nothing physical. Let me explain something about myself. I had been on a regular exercise program since 1975. I love yard work—cutting grass, planting and tending flowers, clipping shrubs, and doing anything else that needs doing outside. I love to sweat—hot weather and sunshine are to be enjoyed because cold weather is over. Being a farm boy at heart, I love the woods—being in the woods without ticks is the only justification for cold weather! Name the outdoors sport, and I have likely tried it—tennis, golf, hiking, fishing, hunting, etc. (I did not say I was good at any of them, but that I tried them.)

My instructions were simple, clear, and emphatic. No “ifs” were involved. Exercise programs were to halt—completely. Sports activities were to halt—completely. Sweating was to halt—completely. Yard work was to cease immediately. I was to learn to slow down, walk correctly, and keep cool (literally). In time, with medical permission, I would again exercise regularly. However, this would occur only when I learned to improve my balance, to slow down, and to stop all forms of sweating activity.

My physical therapy was delayed because of the dislocated

shoulder. I got up from my desk,

turned as I got to my feet, and fell.

I do not remember much about that fall except four things: (1) I was in

too big a hurry; (2) dislocating a shoulder hurts—a lot!; (3) that fall [at

work] surely caused a lot of commotion; and (4) I do not want to fall again!

When I finally began physical therapy, I felt sorry for my first therapist. Through a process of about 20 rhythmical tests, she was to make recommendations. The problem: I have no rhythm! After about half the tests, she kindly, apologetically looked at me and said, “I am sorry, but I do not want to discourage you. I think we better stop these tests.”

She was a helpful, good friend, but I bet she never had a clumsier patient than me! Though she has moved to another state, she will forever remember the man with no rhythm! Maybe I will be in her catalogue of examples used to encourage others!

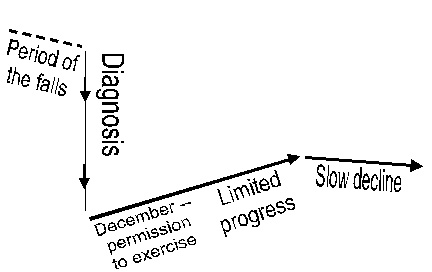

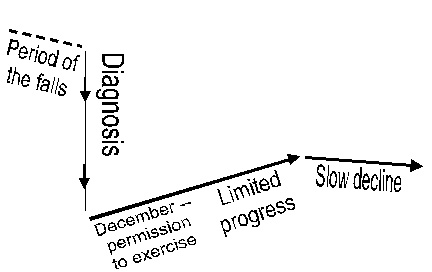

For the rest of the summer and early fall, the active man who loved summer weather restricted his physical activities and sat inside. While I did that, it seemed my physical health was in a steep decline. Were I to graph the situation, it would be a graph like this:

My initial period of inactivity was extremely discouraging. I experienced things I never had experienced before. Muscles involuntarily moved as they tried to determine where they were and what they were supposed to be doing—I had never experienced twitching! My speech declined, faced new challenges, and refused to respond to speech therapy. Reflux problems increased. Then there were the nightly leg cramps or “charlie horses” that came in the early morning hours when I was asleep!

It seemed to me everything physical was out of control, and I could do nothing about it. I felt like large chunks of my life fell off, and all I could do was watch them fall. I do not remember a time in my life when I felt quite so helpless. Merely existing during this time was a new experience.

May I end this chapter by declaring that I had (and continue to have) many good friends who were and are supportive and encouraging. My friends amaze me with all the creative ways in which they demonstrate caring. Though it took me longer to do less, my employers curtailed my responsibilities without expressing concern.

Nor can I begin to say enough about the way Joyce (my wife) supports me. We laugh a lot. She interacts with me as though nothing is wrong. She goes on with life and our relationship as though nothing has changed. No, she is not in denial. It is just that there are no “ifs” in her conversation. She, like me, lives a day at a time, and lets the future unfold as it will. We take care of today, and we will take care of tomorrow when it gets here.

We both live in the “now,” not in the future. It would be extremely difficult for me to live in the “now” if she did not do that, also!

| Next Chapter |